By Lucy Toop

When we’re short of time, we often want straightforward answers and, whether we’re preparing students for mocks or final exams, ensuring that they understand the plot and key characters of Macbeth will be a priority. But students still need opportunities for deeper learning – exploration engages students and gives them the confidence to ask questions of the text for themselves.

Here are three key ideas for encouraging exploration that can work in the classroom or at home:

1. Investigating characterisation

Look beyond Macbeth and Lady Macbeth to ‘minor’ characters, allowing students to explore the complexity of the play, and strengthen their understanding of individual characters as part of a cast.

Macduff is a great starting point: often neglected, he provides one of the play’s most powerful moments when he learns of his family’s slaughter. How does his character arc develop from a silent presence (Act 1 Scene 6) to Macbeth’s nemesis (Act 5 Scene 8)? Some broad discussion points might be:

- What does Macduff’s response to Duncan’s murder suggest about him early on?

- How does Shakespeare shape our emotional response to Macduff through the murder of his innocent – and abandoned – family?

- How does the witches’ prophecy – “Beware Macduff” – set up a chain of events that moves the plot along?

In more detail, help students to trace how Shakespeare presents and uses Macduff as each act unfolds:

- Active role: 2.3, 4; 4.3; 5.4, 6, 7, 8, 9 (what does he say, and how: is his view of events trustworthy?)

- Talked about: 3.6; 4.1, 2 (what emotions does he inspire in others?)

- On stage but silent: 1.6 (what is Macduff doing in this scene? How does he look, behave?)

Students could create graphic representations of Macduff’s character arc – a flow-chart, a storyboard, a graph – for display and revision. They can then use this technique to explore other characters, major and minor.

2. Making context relevant

It’s easy for the task of independent research to overwhelm students or produce generic contextual information. Instead of reading context onto the play, get students to first extract context from the text by ‘asking’ it questions:

Leadership:

Which characters are ‘leaders’ and how do they behave? What can the three contrasting kings – Duncan, Macbeth and Malcolm – tell us about Renaissance ideals of kingship?

Gender and power:

How do the play’s marriages (the Macbeths, the Macduffs) work? What can they tell us about how women and men in Shakespeare’s day were expected to behave, and how they actually behaved?

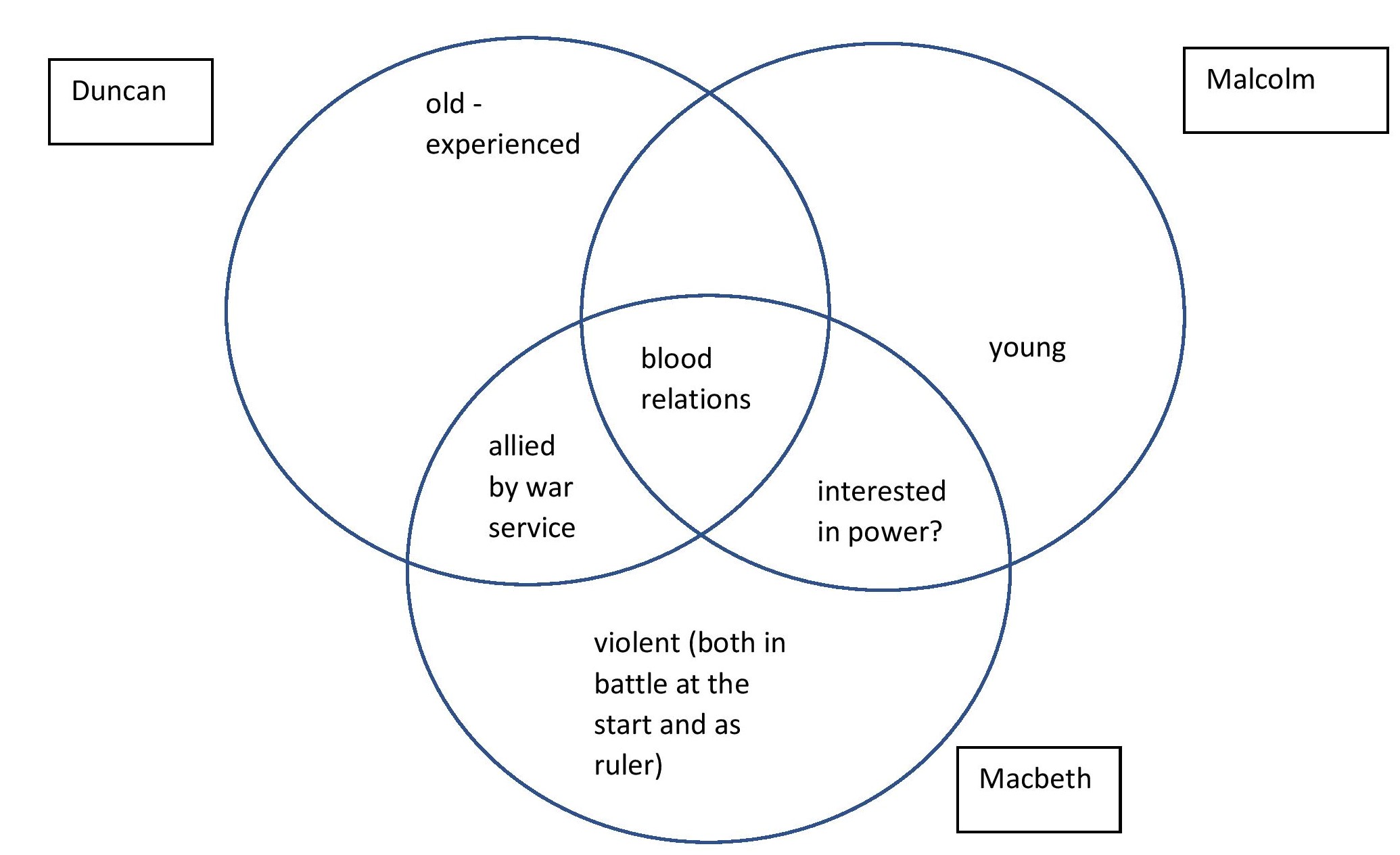

Creating a Venn diagram to explore similarities and differences between kings or relationships might help students to organise their ideas and give a focus for further research:

Give students a few preliminary ideas (the ones here or your own), then get them to work in groups or individually to come up with more similarities and differences.

Once they have gathered ideas and questions from the text, they then have a focus for further research into wider contexts. For instance, how does the idea of the ‘divine right’ of kings fit the presentation of kings in the play? How might the experience of a female ruler in Elizabeth I have affected contemporary perceptions of powerful women?

3. Exploring dialogue

We often focus on the soliloquies, but exploring the play’s dialogues is a great way to understand how Shakespeare creates meaning through the structures of language. See for example:

- Macbeth/Lady Macbeth – 1.7, 2.2, 3.2

- Macbeth/Banquo – 1.3, 3.1

- Malcolm/Macduff – 4.3

- Macduff/Macbeth – 5.8

These dialogues are all between characters with key relationships in the play. How does Shakespeare tell us more about them through conversation? When reading one of these scenes, get students to identify what ‘type’ of conversation is taking place – interrogation, seduction, negotiation, etc. or even a mixture. Things to consider include:

- who has more/the most to say? Is this because one has more power, or one is hiding something (any asides?)?

- pronoun usage (and any shifts)

- use of questions (Macduff in 4.3)

- if the dialogue is verse, who ‘answers’ who by completing the line (look at the dialogues between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in 1.7 and 2.2, for instance)? Is this like-mindedness, complicity, eagerness to please? Who disrupts the pentameter? Is this shock, unease, a desire to distance from the other speaker?

As an extension exercise to embed understanding of these techniques, students could write modern-day versions for ‘off-stage’ dialogues – Macduff leaving his wife, for instance, or a scene between Lady Macbeth and her guest, Banquo.

Providing students with tools to explore the text independently is empowering for them – and, whether we’ve been teaching Macbeth for two years or twenty, seeing it through fresh eyes can be illuminating for us too.

Lucy Toop is a freelance writer and secondary English teacher in South London.

If you want more help with Macbeth check out our super Macbeth Study Guide, Workbook and Practice Tests.